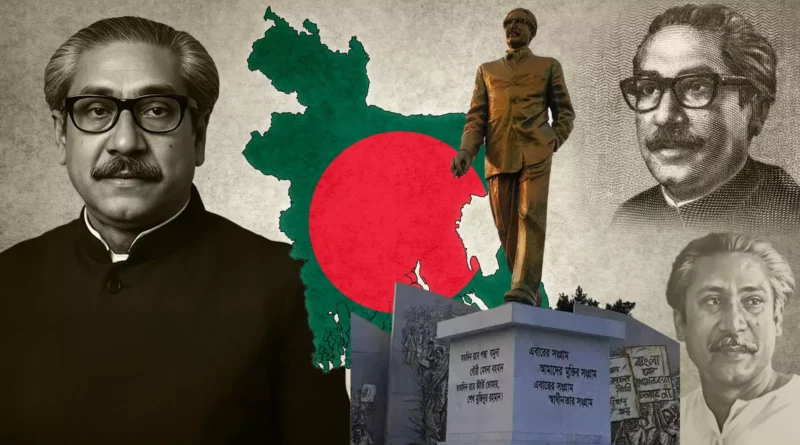

The Vision of Sheikh Mujibur Rehman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, fondly known as Bangabandhu (Friend of Bengal) and revered as the Father of the Nation, was the visionary architect of independent Bangladesh. Born on March 17, 1920, in Tungipara village, Gopalganj (then part of British India), Mujib’s life was a relentless pursuit of emancipation for the Bengali people. From his early days as a student activist to leading the 1971 Liberation War, his vision evolved from demanding autonomy within Pakistan to forging a sovereign nation grounded in four foundational principles: Nationalism (emphasizing Bengali identity), Socialism (for economic equity), Democracy (participatory governance), and Secularism (religious harmony). These ideals, enshrined in the 1972 Constitution of Bangladesh, reflected his dream of a “Sonar Bangla” (Golden Bengal)—a prosperous, just, and self-reliant society free from exploitation.

Mujib’s vision was not abstract; it was forged in the fires of colonial oppression, linguistic injustice, and economic disparity. His autobiography, The Unfinished Memoirs, reveals a leader who spoke truth to power, blending charisma with pragmatic foresight. Assassinated on August 15, 1975, along with most of his family, Mujib’s legacy endures through Bangladesh’s progress toward middle-income status and its global recognition as a development miracle. This note explores his vision across political, economic, social, cultural, and educational dimensions, drawing on his speeches, policies, and historical actions.

Early Life and Political Awakening

Mujib’s journey began amid the socio-political turbulence of pre-partition India. Educated at Gopalganj Missionary School and Islamia College in Calcutta, he was drawn into activism during the 1940s. As a founding member of the East Pakistan Muslim Students’ League (1948) and joint secretary of the Awami Muslim League (1949), he championed Bengali rights against the dominance of West Pakistan. His first arrest in 1948 for protesting the imposition of Urdu as the state language marked him as a defender of linguistic identity—a cornerstone of his nationalism.

His experiences, including multiple imprisonments, honed a vision of empowerment for the marginalized. As he reflected in The Unfinished Memoirs, he rejected both communism and capitalism, advocating socialism as a tool against oppression: “I myself am no communist; I believe in socialism and not capitalism. Capital is the tool of the oppressor.”

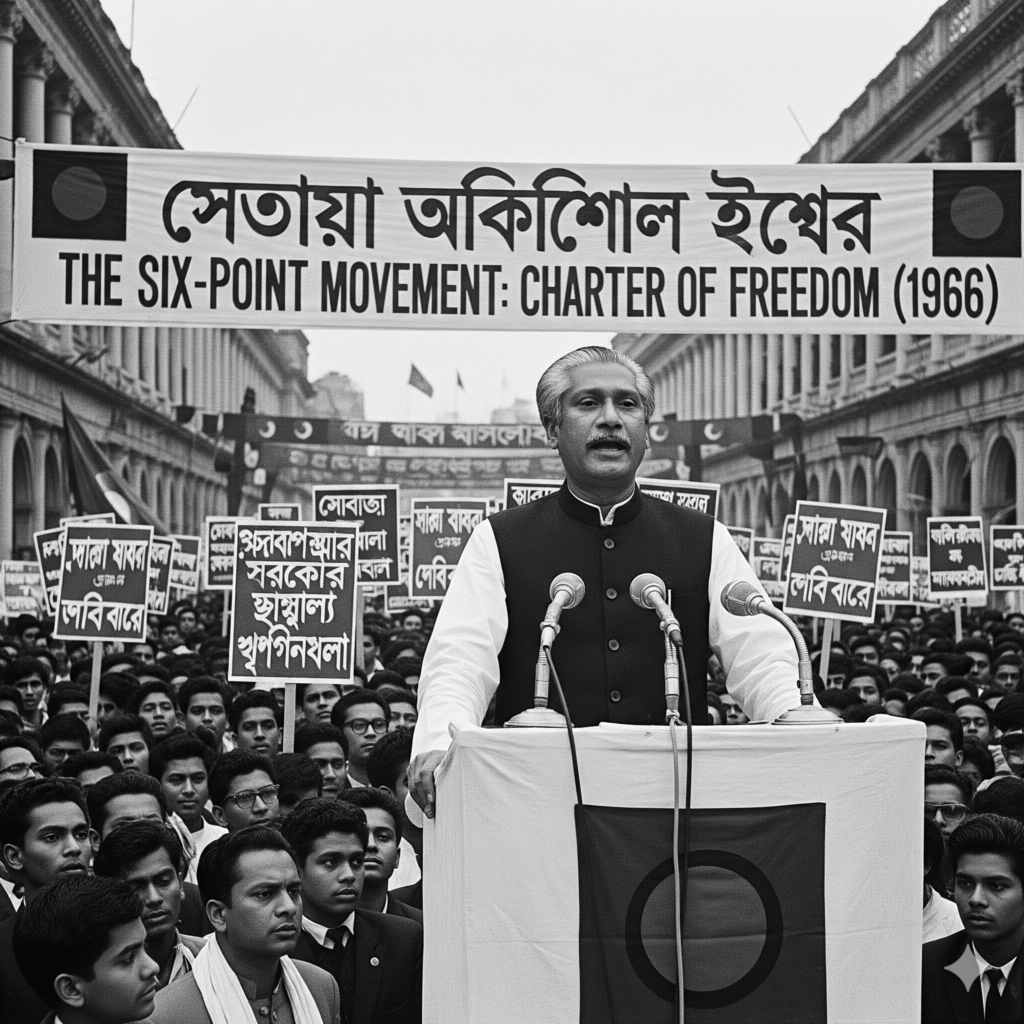

The Six-Point Movement: Charter of Freedom (1966)

In February 1966, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman presented the charter of demands at a conference of opposition parties in Lahore. He later publicized the program, calling it “Our Demands for Existence.” The six points included:

- Federal government and parliamentary democracy: The constitution should establish a true federation with a parliamentary form of government based on universal adult franchise.

- Limited federal powers: The federal government would only control defense and foreign affairs, leaving all other legislative powers to the federating states.

- Separate currencies: Two separate but freely convertible currencies for the two wings, or a single currency with constitutional safeguards to prevent capital flight from East to West Pakistan.

- Provincial control of taxation: The federating units would have the power of taxation and revenue collection, with the federal government receiving a share to meet its expenses.

- Separate foreign exchange accounts: The two wings would maintain separate accounts for foreign exchange earnings, and the federating units would be empowered to conduct their own trade relations abroad.

- Separate militia: East Pakistan would have its own militia or paramilitary force for its defense.

The Liberation War and Declaration of Independence (1971)

Mujib’s historic March 7, 1971, speech at Ramna Racecourse—broadcast globally—ignited the revolution: “This time the struggle is for our freedom. This time the struggle is for our independence.” Facing Pakistani crackdown on March 25, he proclaimed Bangladesh’s independence, becoming its president in absentia. Imprisoned in West Pakistan and facing a death sentence in the Agartala Conspiracy Case, Mujib’s charisma unified the Mukti Bahini (liberation forces) and secured Indian support.

The nine-month war ended in victory on December 16, 1971. Mujib’s release in January 1972 marked his triumphant return, solidifying his role as the embodiment of Bengali resilience. His vision here was clear: a nation where Bengalis could live with dignity, free from colonial yoke.

As prime minister (1972–1975) and later president (1975), Mujib tackled a war-ravaged economy (GDP growth at -13% in 1972) with bold reforms. His vision was holistic: political stability, economic socialism, social justice, and cultural revival.

Political Vision

Democracy and Secularism: The 1972 Constitution embedded the four principles, ensuring multiparty elections, fundamental rights, and religious neutrality. Mujib viewed secularism as state impartiality, not anti-religion, to foster unity among Hindus, Muslims, and minorities. Nationalism: Bengali language and culture as state pillars, rejecting religious politics that divided people.

Economic Vision

- Waived agricultural taxes; upgraded agriculturists to first-class status.

- Foodgrain production rose from 7.5 million tons (1972) to 9.5 million (1975).

- Emphasized rural development: “We will turn this war-ravaged country into a golden one.”

His global outreach—visits to India, the US, and USSR—secured aid, reflecting a non-aligned foreign policy.

Educational Vision

Education was Mujib’s tool for human resource development. In 1972–1973 speeches, he stressed universal access: “Education is a fundamental human right… for social, political, and economic development.” He formed the Qudrat-e-Khuda Education Commission (1972), recommending:

- Free, compulsory primary education.

- Vocational training for self-reliance.

- Rural immersion for teachers/students to bridge urban-rural divides.

The Commission’s 1974 report—309 pages—remains a blueprint, though unimplemented due to his assassination.

Death of Mujib Rehman

Sheikh Mujibur Rahman was assassinated on August 15, 1975, in a military coup at his residence in Dhaka, Bangladesh. The attack, orchestrated by a group of junior army officers, also claimed the lives of most of his family, including his wife, Begum Fazilatunnesa, three sons (Sheikh Kamal, Sheikh Jamal, and Sheikh Russel), two daughters-in-law, and his brother, Sheikh Nasser. The coup marked a tragic end to his leadership, just three years after Bangladesh’s independence.

Mujib was shot multiple times, and the assailants faced little immediate resistance due to the suddenness of the attack and the involvement of trusted security personnel. The coup leaders, dissatisfied with Mujib’s governance, economic challenges, and the one-party state (BAKSAL) introduced in 1975, aimed to seize power. The plot was linked to factions within the military and political opponents, though full details remain debated.

His death plunged Bangladesh into political turmoil, leading to a series of coups and military rule until democracy was restored in 1991. The event remains a pivotal scar in Bangladesh’s history, with ongoing trials (e.g., 1998 convictions of 15 conspirators) seeking justice. Mujib’s vision for a “Sonar Bangla” endures, carried forward by his daughter, Sheikh Hasina, until her ousting in 2024.

For deeper context, refer to his Unfinished Memoirs or historical accounts like those by Willem van Schendel. If you meant a specific aspect of his death (e.g., conspirators, aftermath), please clarify!