The Untold Story of Pakistan’s Independence (1947)

The history of Pakistan’s independence in 1947 is rich and complex, shaped by political, social, and religious factors. While the widely known narrative focuses on the role of prominent leaders like Muhammad Ali Jinnah and the formation of Pakistan as a separate Muslim-majority state, there are several untold and lesser-known aspects of this transformative period in South Asian history.

The Legacy of British Colonial Rule

The British Empire ruled India for nearly 200 years, leaving a deeply fractured society. The British managed a complex system of governance, using divide-and-rule tactics to maintain control over a vast and diverse population. One of the main tools for this was the divide between Hindu and Muslim communities.

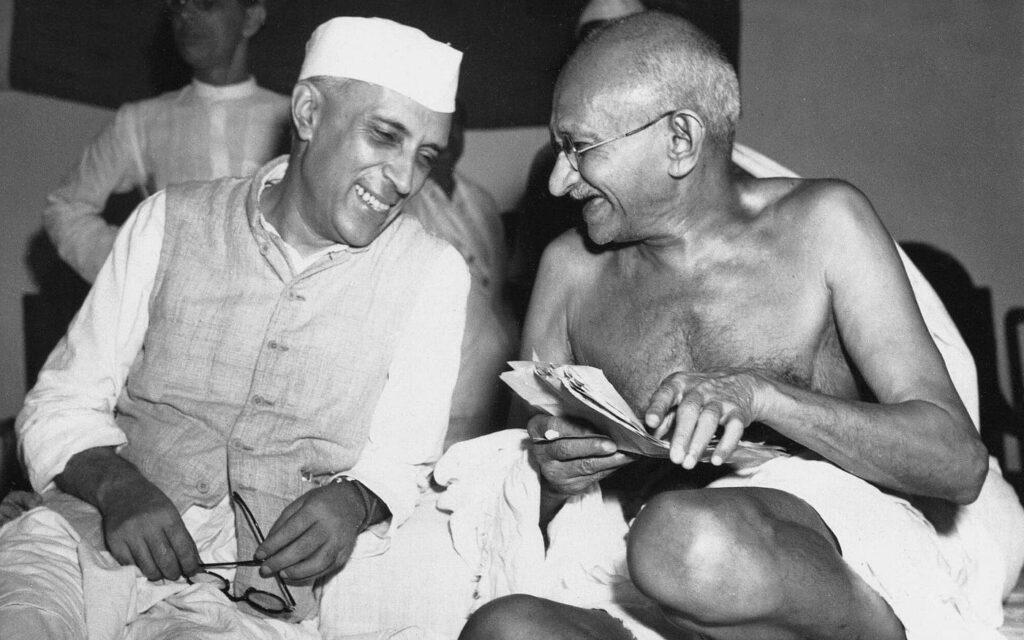

However, during the British colonial rule, India had seen increasing political and social movements for independence. Notable among them were the Indian National Congress (INC), led by figures like Jawaharlal Nehru and Mahatma Gandhi, and the All India Muslim League, led by Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

What is often not discussed in mainstream narratives is the complexity of the Muslim community’s concerns, which were not solely religious but deeply political. The Muslim League initially sought greater political representation within a united India, but as Hindu-majority India was gaining momentum for self-rule, Muslims feared they would be politically sidelined.

Jinnah’s Vision for Pakistan

While Jinnah is known as the founder of Pakistan, his path to that vision was not straight-forward. Initially, Jinnah was a prominent leader in the Indian National Congress and had worked closely with figures like Gandhi for the independence of India. His shift towards the idea of a separate Muslim-majority state came gradually, especially after the 1937 provincial elections, where the Muslim League performed poorly compared to the INC.

Jinnah believed in the Two-Nation Theory, which argued that Hindus and Muslims were not simply different religious groups but distinct nations with different cultures, languages, and ways of life. He championed this cause during the 1940s, leading to the Lahore Resolution (March 23, 1940), where the demand for a separate Muslim homeland was officially declared. However, Jinnah’s vision for Pakistan was of a secular state with protection for minorities, not a theocratic one. This aspect of his vision is often overshadowed by later developments in the country’s political and social history.

The Role of Muslim Women and Social Movements

Another untold aspect of Pakistan’s independence is the role of Muslim women in the movement. Though they were often marginalized in the public narrative, many Muslim women played critical roles in the political and social upheavals of the 1940s.

Muslim women have historically and continue to play vital roles in social movements, challenging patriarchal norms, and advocating for gender equality, peacebuilding, and social justice within an Islamic framework. Their activism is often rooted in egalitarian interpretations of the Quran, countering the notion that their movements are solely a “Western export”.

Historical roles

- Early Islam to the colonial era:

- In the early days of Islam, figures like the Prophet Muhammad’s wife, Aisha, were scholars who taught both men and women, and even had a political presence.

- Successful businesswomen like Khadija bint Khuwaylid demonstrated economic independence and influence.

- Over time, patriarchal interpretations of religious texts and conservative societal norms increasingly confined women, but some women broke these conventions.

- During the colonial period, Muslim women were instrumental in anti-colonial and nationalist movements, often linking their struggle for rights to the wider fight for independence.

- The Pakistan Movement:

- Muslim women were pivotal in the establishment of Pakistan, organizing rallies, founding women’s branches of the Muslim League, and advocating for social and political rights.

- Prominent leaders like Fatima Jinnah actively mobilized women across all classes and became known as the “Mother of the Nation”.

- After independence, organizations like the All Pakistan Women’s Association (APWA), founded by Begum Rana Liaquat Ali Khan, continued to work for women’s social, political, and legal status.

Contemporary movements and activism

Today, Muslim women are involved in diverse forms of activism globally, often utilizing feminist interpretations of Islam to advance their causes.

- Islamic feminism:

- Islamic feminism is a growing movement that advocates for women’s rights and gender equality from within an Islamic framework, challenging patriarchal readings of the Quran and Hadith.

- Scholars and activists like Amina Wadud, Fatema Mernissi, and Riffat Hassan reinterpret religious texts to restore the egalitarian ideals they argue were present in early Islam.

- Groups such as Sisters in Islam (SIS) in Malaysia and Musawah globally work to reform discriminatory family laws and empower women within their communities.

- Rights-based and political activism:

- The women’s movement in Pakistan successfully pushed for pro-women legislation, including laws against sexual harassment and domestic violence. The Aurat March is a contemporary example of this activism.

- In the Sahel region, Muslim women’s groups advocate for access to education, social services, and family law reforms, using both secular and religious arguments.

- Across the Muslim world, women are asserting their right to participate in public religious life, leading prayers for women in mosques and pushing for greater representation in decision-making bodies.

- Peacebuilding and social justice:

- Muslim women are active in peacebuilding and conflict resolution, often at the grassroots level, by creating counter-narratives to extremism, providing social assistance, and mediating community disputes.

- Through art, literature, and media, young Muslim women are raising awareness about social injustices, corruption, and gender-based violence.

Challenges and impacts

Despite significant achievements, Muslim women in social movements face ongoing challenges:

- Cultural and political opposition:

- Activists often face resistance from conservative religious leaders and patriarchal societal norms that emphasize traditional gender roles.

- Women who challenge the status quo are sometimes accused of promoting a “Western agenda” or undermining family values.

- Navigating identity:

- There can be friction between secular and Islamic feminist groups, particularly regarding strategy and engagement with religious texts and institutions.

- Activists often have to “bargain with patriarchy,” strategically conforming to certain expectations (like modesty in dress) in order to gain legitimacy and create space for their work.

- Structural and institutional barriers:

- Weak enforcement of pro-women laws and a lack of resources for women’s organizations hinder progress.

- Institutional patriarchy within religious and political structures remains a significant barrier to women’s leadership and full participation.

The impact of Muslim women’s activism is substantial, leading to concrete legal and social reforms, challenging monolithic stereotypes of Muslim women, and fostering a nuanced understanding of gender justice from within an Islamic context. Their work continues to transform both local communities and the global discourse on women’s rights and empowerment.

The Partition and Its Human Cost

The partition of India into two nations, India and Pakistan, on August 14, 1947, is one of the bloodiest chapters in the region’s history. The official narrative often highlights the political negotiations, but the human cost of partition is an untold story that continues to reverberate in both India and Pakistan to this day.

Key aspects of partition that are not often discussed include:

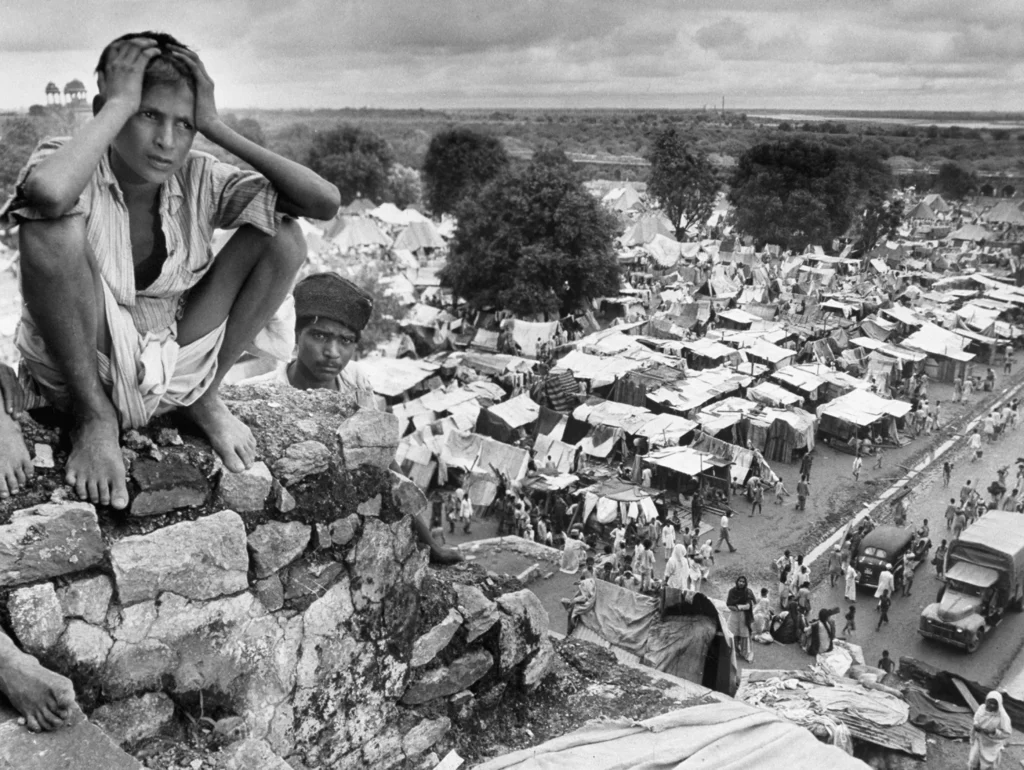

- Mass Migration and Violence: The division of territories between India and Pakistan led to one of the largest migrations in human history. Around 14 million people were displaced along religious lines. The migration was accompanied by intense violence, leading to the deaths of hundreds of thousands of people. Hindus and Sikhs fled to India, while Muslims migrated to Pakistan. The violence was particularly brutal in regions like Punjab and Bengal.

- Unresolved Kashmir Issue: The partition also left the princely state of Jammu and Kashmir in a state of limbo. The decision of whether Kashmir would join India, Pakistan, or remain independent became one of the core issues that shaped the politics of South Asia in the subsequent decades.

- The Role of the British: The British are often criticized for their role in the partition. The rushed and poorly planned division of territory and the arbitrary drawing of borders by the Radcliffe Line led to mass confusion, displacement, and violence. The British left India quickly, without putting in place the necessary mechanisms to handle the aftermath of partition, leaving the newly formed governments of India and Pakistan to deal with the chaos.

The Impact of the Refugee Crisis

The refugee crisis that followed partition had long-lasting impacts on the social fabric of Pakistan. The refugees who arrived in Pakistan were often traumatized by the violence and loss they experienced during their migration. Many were forced to start anew with little to no resources.

Pakistan’s urban areas, particularly cities like Karachi, saw a sharp rise in population, leading to pressure on infrastructure and resources. This sudden influx of refugees also led to the development of new religious, cultural, and political identities in Pakistan. The integration of refugees into Pakistani society was not smooth, and this continues to influence the socio-political dynamics of the country today.

The Role of the Indian National Congress and Jawaharlal Nehru

Jawaharlal Nehru and the Indian National Congress (INC) played pivotal, interconnected roles in India’s struggle for independence and its subsequent nation-building. Nehru emerged as a key leader within the INC, transforming its ideology towards socialism and full independence, and later, as India’s first Prime Minister, he shaped the country’s foundational democratic, secular, and economic policies.

Role of Jawaharlal Nehru in the Indian National Congress

- Freedom struggle leadership: Nehru joined the INC in 1919 and quickly rose to prominence, becoming a close associate of Mahatma Gandhi.

- Advocated for Purna Swaraj: First becoming INC President in 1929, he led the party in passing the “Purna Swaraj” (complete independence) resolution in Lahore, moving the goal beyond mere Home Rule within the British Empire.

- Organized mass movements: He was a central figure in major non-violent civil disobedience campaigns like the Non-Cooperation Movement (1920–1922) and the Quit India Movement (1942), which often resulted in his imprisonment.

- Promoted socialist ideology: In the 1930s, Nehru worked to infuse the INC’s platform with socialist principles to address India’s deep socio-economic inequalities.

Role of the Indian National Congress during the independence era

- A platform for nationalism: Founded in 1885, the INC initially aimed for greater autonomy and civil rights within the British Raj. Over time, it became the primary political voice for Indian nationalism.

- Negotiating independence: Under the leadership of figures like Gandhi and Nehru, the INC was the main party negotiating with the British for India’s independence.

- Forming the first government: After independence and the partition of British India in 1947, Nehru became the first Prime Minister, leading the interim government and subsequently winning India’s first general election in 1952.

Nehru’s role and policies as Prime Minister (1947–1964)

Holding the prime ministership for 17 years, Nehru was the “architect of modern India,” steering the nation’s post-independence development.

- Establishing democracy and secularism: He was instrumental in rooting fundamental values in the Indian polity, including a commitment to a plural, open, and democratic state. He also championed a secular ideal, ensuring religious freedom and protecting minority rights, often against internal opposition.

- Economic policy: He advocated for a mixed economy that combined a strong public sector with private enterprise. His focus on heavy industry, through five-year plans, aimed to create a self-reliant and industrialized nation.

- Social and educational reforms: Nehru championed agrarian land reforms to address inequality and was a strong advocate for education. His government established premier institutions like the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs), Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), and the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS).

- Foreign policy and the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM): During the Cold War, Nehru promoted a non-aligned foreign policy to position India as a leader among newly independent nations, advocating for peace and international cooperation and refusing to ally with either superpower. He is considered one of the founding fathers of the NAM, whose principles were based on Nehru’s “Panchsheel” (Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence).

Legacy and contemporary context

- Long-term political dominance: Nehru’s leadership cemented the INC’s status as India’s dominant political party for decades, though its influence waned significantly in the late 20th and early 21st centuries in the face of competition from other parties, most notably the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP).

- Nehruvian values: The core values of democracy, secularism, and planned economic development that Nehru championed remain central to political discourse in India and are often referred to as the “Nehruvian consensus”.

- Foundational institutions: The institutions established during his tenure continue to be pillars of India’s development and are seen as a key part of his lasting legacy.

The Role of the Military and the Intelligence Services

The military and intelligence services are essential parts of a state’s security apparatus, primarily responsible for defense against external threats and gathering information to protect national interests. While the military is the most coercive instrument of the state, intelligence services are responsible for providing decision-makers with credible information on potential threats, enabling policymakers to define national security interests and strategies.

The military

Core responsibilities

- National defense: The primary and constitutional role of the military is to defend the state’s sovereignty and territorial integrity from external aggression and the threat of war.

- Deterrence: A strong military acts as a deterrent to potential adversaries. In the context of nuclear powers, a credible nuclear strategy is also considered part of a nation’s defensive posture.

- Internal security: The military can be called upon to support civil authorities in responding to internal threats like insurgency, terrorism, and ethnic or sectarian conflicts.

- Peacekeeping and humanitarian aid: Armed forces are often active participants in United Nations peacekeeping missions and conduct humanitarian rescue and disaster relief operations both at home and abroad.

- Military diplomacy: Beyond direct combat, militaries engage in “defense diplomacy” to support foreign policy objectives. This includes high-level defense dialogues, joint training exercises, arms sales, and security cooperation to build trust and prevent conflicts with other nations.

Governance and civilian relations

- In a healthy democracy, civilian control over the military is paramount. The military provides expert advice on defense and national security, but ultimate policy decisions are the responsibility of the elected civilian leadership.

- The military is expected to be an apolitical servant of the state, separate from political party interests. In countries with weak democratic institutions, however, the military may exert excessive influence on political life, sometimes leading to coups or the establishment of authoritarian rule.

Intelligence services

Core responsibilities

- Information gathering: Intelligence agencies collect and analyze information from both open (OSINT) and secret sources, including human intelligence (HUMINT), signals intelligence (SIGINT), and imagery intelligence (IMINT).

- Threat assessment: The primary task is to produce timely, accurate, and objective analysis of potential threats to the state and its population. This includes identifying and monitoring foreign military capabilities, terrorist groups, foreign agents, and sleeper cells.

- Counterintelligence: A key function is to protect intelligence sources, methods, and government secrets by preventing espionage, subversion, and sabotage by foreign powers or foreign-controlled groups.

- Support for decision-making: Intelligence products help policymakers define national interests, develop coherent national security strategies, respond to crises, and inform military planning.

- Covert operations: In some cases, intelligence services may conduct secret operations to influence political, military, or economic conditions in foreign countries when diplomacy has failed and direct military action is not desired. These activities can range from propaganda to assisting foreign governments or disrupting illicit activities abroad.

Governance and oversight

- Due to their secretive nature and intrusive powers, democratic oversight of intelligence services is critical to ensure accountability and adherence to the rule of law and human rights.

- Oversight mechanisms include executive, parliamentary, and judicial controls, often backed by a sound legal framework defining the services’ mandates, permissible methods, and accountability procedures.

- Maintaining a balance between secrecy and accountability is a constant challenge. Effective oversight aims to prevent the misuse of power, political bias in intelligence analysis, and the risk of intelligence agencies becoming a “secret police” that suppresses political dissent.

A rushed and chaotic partition

- The accelerated timeline: The original plan was for Britain to withdraw by June 1948, allowing time for an orderly transfer of power. However, fearing escalating communal violence, the last Viceroy, Lord Mountbatten, moved the date to August 15, 1947. This left only six weeks to partition the country, its assets, and its infrastructure.

- The secret Radcliffe Line: The new borders were drawn by a British barrister, Sir Cyril Radcliffe, who had no prior knowledge of India and its complex demographics.

- The border, known as the Radcliffe Line, was not publicly announced until August 17, two days after independence. This delay caused confusion and exacerbated violence in areas where villagers suddenly found themselves on the “wrong” side of the new border.

- Decisions on border areas were controversial, such as the awarding of the Muslim-majority Gurdaspur district to India, which provided India with a crucial land route to Kashmir.

A “start from nothing”: Upon independence, Pakistan faced immense institutional challenges. There was no established capital, central bank, or functioning army. The newly formed government, led by Governor-General Muhammad Ali Jinnah and Prime Minister Liaquat Ali Khan, had to build an administrative structure from scratch while grappling with an immediate refugee crisis and hostile relations with India.

The human cost: violence and the refugee crisis

- One of history’s largest mass migrations: Contrary to the initial British assumption that populations would stay put, the partition triggered an unprecedented wave of migration. An estimated 10 to 20 million people crossed the new borders in both directions, making it one of the largest population transfers in history.

- Extreme violence and unspeakable acts: The migration was accompanied by horrific communal violence, particularly in Punjab and Bengal.

- Estimates of deaths range from several hundred thousand to 2 million, and historians note genocidal tendencies in the massacres.

- Survivors’ stories recount gruesome acts, such as the murder of family members to prevent abduction and forced conversion, attacks on refugee trains, and widespread looting and assault.

- An unequipped government: The fledgling Pakistani government was completely unprepared for the scale of the crisis. Refugee camps quickly became overcrowded and unsanitary, leading to the spread of disease and further loss of life.

The role of minority communities

- Christian support for Pakistan: While Sikh and Hindu communities largely opposed partition, some Christian leaders, such as Dewan Bahadur S.P. Singha, voted in favor of joining Pakistan in the Punjab Assembly.

- Singha argued that joining Pakistan would better protect minority rights and believed in Jinnah’s vision for an inclusive state where followers of all faiths could live in harmony.

- Christians, who initially numbered over 300,000 in West Pakistan, played a significant role in nation-building and contributed to the economy, arts, and military.

- The tragic fate of Sikhs: Sikhs were deeply affected by the partition, with their traditional homeland of Punjab being divided and many holy sites falling on the Pakistani side of the border.

- Sikhs suffered disproportionately high casualties during the violence and were forced to migrate en masse, fundamentally altering their community and cultural identity.

- Enduring legacy: Despite Jinnah’s vision of an egalitarian, multi-religious state, the promise was not fully realized by his successors. Decades of discrimination and societal intolerance have eroded the founders’ ideals, and tensions surrounding minority rights, particularly for Christians and Hindus, remain a significant challenge for modern Pakistan.

Ongoing disputes and the struggle for survival

- The Kashmir dispute: The princely state of Jammu and Kashmir became a major point of contention. After Pashtun tribal militias, supported by Pakistan, invaded the state, its Hindu ruler chose to accede to India in exchange for military assistance.

- The resulting Indo-Pakistani War of 1947–1948 solidified a de facto border, but the dispute over Kashmir remains unresolved and has been a source of ongoing conflict.

- Challenges and survival: India’s refusal to release Pakistan’s full share of financial assets and the unfair division of military equipment deliberately placed the new country at a disadvantage.

- Many observers at the time believed Pakistan would not survive for long. However, under Jinnah’s determined leadership, the country faced down these initial challenges and began the difficult process of nation-building.

- The partition was not only a political event but a profoundly human one, shaping the national consciousness and leaving an indelible mark on the memories of those who lived through its hopeful yet harrowing days.

The path to independence

- al idea behind the Pakistan movement was the “Two-Nation Theory,” which argued that Hindus and Muslims were two separate nations with distinct cultures, social customs, and historical backgrounds.

- This concept was articulated by figures like Sir Syed Ahmed Khan and philosopher Allama Muhammad Iqbal, who saw that a parliamentary system in a united India would inevitably lead to Hindu-majority dominance.

- Iqbal, in his 1930 presidential address to the Muslim League, explicitly proposed the idea of a separate Muslim state in the Muslim-majority regions of northwestern India.

- The Pakistan Resolution: On March 23, 1940, the Muslim League formally adopted the “Lahore Resolution,” commonly known as the Pakistan Resolution, which demanded the creation of independent states for Muslims in the northwestern and eastern zones of India.

- Muslim League’s rise to power: While the Indian National Congress launched the “Quit India” movement during World War II, the Muslim League gained political strength under Jinnah’s leadership. In the 1945–46 elections, the League campaigned on the single issue of Pakistan and won nearly all the seats reserved for Muslims, validating its claim to be the sole representative of the Muslim community’s interests.

- Failed negotiations and Mountbatten Plan: The British attempted to negotiate a compromise through the Cabinet Mission Plan of 1946, proposing a loose federation with autonomous provincial groups. However, disagreements between the Congress and the League caused the plan to fall apart. Fearing civil war, the last Viceroy, Lord Louis Mountbatten, then prepared a plan for the partition of India, which was announced on June 3, 1947.

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks! https://www.binance.com/cs/register?ref=OMM3XK51