The Story of Katherine Johnson

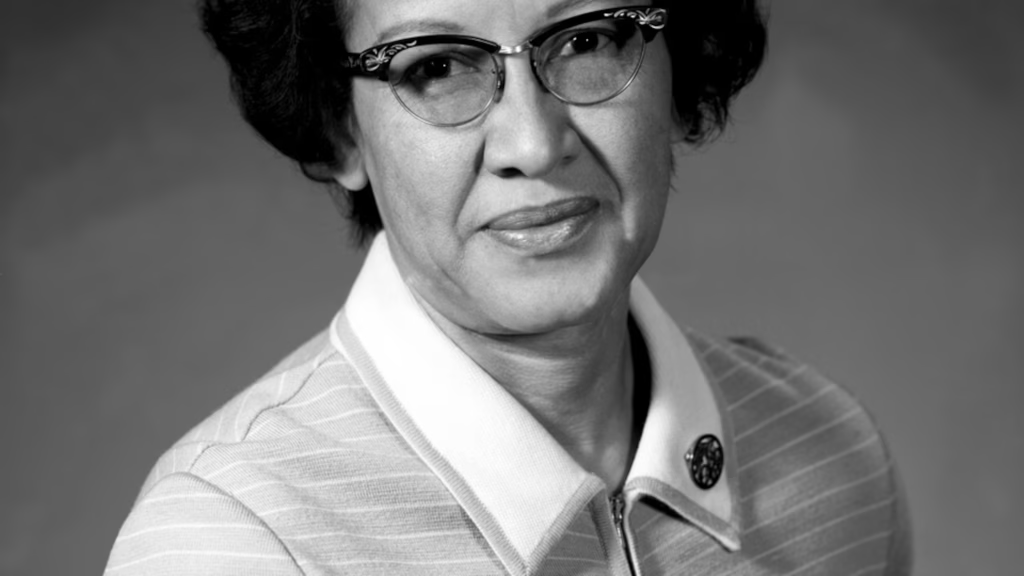

Katherine Johnson’s story is one of brilliance, perseverance, and breaking barriers. Born on August 26, 1918, in White Sulphur Springs, West Virginia, Katherine Coleman displayed an extraordinary aptitude for mathematics from a young age. Growing up in a segregated America, she faced systemic racism and gender discrimination, yet her intellect and determination propelled her to become a pivotal figure in NASA’s space program and a symbol of resilience.

Education

Katherine’s love for numbers was evident early on. By age 10, she was already in high school, excelling in a system that offered limited opportunities for Black students. Her family prioritized education, and her father, Joshua Coleman, worked multiple jobs to support her schooling. At 14, Katherine graduated from high school and enrolled at West Virginia State College, a historically Black institution. There, she took every math course available, mentored by professors like W.W. Schieffelin Claytor, who recognized her potential and created advanced math classes just for her. In 1937, at 18, she graduated summa cum laude with degrees in mathematics and French.

After college, Katherine briefly taught school, as opportunities for Black women in mathematics were scarce. In 1939, she was one of three Black students selected to integrate West Virginia University’s graduate program, a significant step in a state where segregation was law. However, she left the program early to start a family with her first husband, James Goble, whom she married in 1939. They had three daughters: Constance, Joylette, and Katherine.

Katherine Johnson Husbands

James Francis Goble

- Katherine Coleman married James Francis Goble in 1939.

- He passed away from an inoperable brain tumor in 1956.

James A. Johnson

- She married her second husband, U.S. Army veteran Lieutenant Colonel James A. “Jim” Johnson, in 1959.

They were married for 60 years until his death in 2019.

Joining NASA

In 1953, after James Goble’s death from cancer, Katherine’s life took a pivotal turn. She applied to the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), NASA’s predecessor, and was hired as a “computer”—a human calculator—at the Langley Research Center in Hampton, Virginia. Black women computers worked in a segregated unit, the West Area Computing Unit, performing complex calculations for aerospace engineers. Katherine’s precision and problem-solving skills quickly set her apart.

Contributions

Project Mercury (1961-1963)

Project Mercury was the first human spaceflight program of the United States. It ran from 1958 to 1963. The program aimed to put a man into Earth’s orbit and return him safely, ideally before the Soviet Union. This was a key part of the Space Race during the Cold War.

First American in space: Alan Shepard became the first American in space on May 5, 1961. The suborbital flight lasted 15 minutes.

First American to orbit Earth: John Glenn was the first American to orbit the Earth. On February 20, 1962, he completed three orbits in his Friendship 7 capsule.

Longest mission: Gordon Cooper’s 34-hour mission in May 1963 was the longest of the program. It showed that humans could function well in space for an extended time.

Successful recoveries: The program safely re-entered the atmosphere. It recovered both the astronaut and spacecraft from the ocean.

Public engagement: Millions of people followed Mercury missions via radio and TV. This captured public interest and created a new profession of “astronaut” in the United States.

Apollo Program (1969-1972)

The Apollo Program was the culmination of the United States’ efforts to land humans on the Moon and return them safely to Earth before the end of the 1960s. Following President John F. Kennedy’s 1961 challenge, the program was executed by NASA from 1961 to 1972, with the first crewed mission launching in 1968.

Apollo 11 (1969): This mission famously landed Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin on the Moon on July 20, 1969, while Michael Collins remained in lunar orbit. Armstrong’s first step was broadcast to a worldwide television audience.

Lunar exploration: The Apollo astronauts conducted scientific research, collected 382 kg (842 pounds) of lunar rocks and soil, and deployed scientific instruments on the Moon’s surface. The later “J-missions” (15, 16, and 17) included a Lunar Roving Vehicle (rover) to extend the astronauts’ range of exploration.

Apollo 1 fire (1967): Before any crewed Apollo flight, a flash fire during a launch pad test killed the three-person crew—Gus Grissom, Ed White, and Roger Chaffee. This tragedy forced a reevaluation of spacecraft and safety procedures, delaying the program.

Apollo 13 (1970): The mission, intended as the third lunar landing, was crippled by an oxygen tank explosion en route to the Moon. The crew and Mission Control worked together to improvise a safe return by using the Lunar Module as a “lifeboat”. Subsequent use: After the final lunar landing in 1972, Apollo spacecraft were used for the Skylab program in 1973–1974 and the Apollo-Soyuz Test Project in 1975.

Space Shuttle and Beyond (1981–2011)

The period following the Apollo Program saw a shift in priorities for human spaceflight, moving from short, high-profile lunar missions toward developing permanent infrastructure in low-Earth orbit. This era was defined by the Space Shuttle program, which focused on reusability, and has since been followed by a new phase of international collaboration and the rise of commercial spaceflight.

Built the International Space Station (ISS): Shuttles were instrumental in carrying large modules, parts, and crews to build the largest structure ever put into space.

Repaired the Hubble Space Telescope: Several missions serviced and upgraded the Hubble Space Telescope, dramatically extending its life and enabling groundbreaking astronomical discoveries.

Scientific experiments: The shuttle’s on-board laboratories enabled countless microgravity experiments in science, astronomy, and physics.

Legacy of Katherine Johnson

For decades, Katherine’s contributions went largely unrecognized outside NASA. That changed with the 2016 book Hidden Figures by Margot Lee Shetterly and its film adaptation, which brought her story to a global audience. The film, starring Taraji P. Henson as Katherine, highlighted her role alongside colleagues like Dorothy Vaughan and Mary Jackson.

In 2015, at age 97, Katherine received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Barack Obama, the nation’s highest civilian honor. NASA named a computational research facility after her in 2017, and she received the Congressional Gold Medal in 2019. West Virginia University and other institutions have also honored her with statues and scholarships.

Katherine retired from NASA in 1986 after 33 years of service. She spent her later years advocating for STEM education, particularly for underrepresented groups. She passed away on February 24, 2020, at age 101, leaving a legacy that continues to inspire.

Motivation from her Life

Katherine Johnson was an extraordinarily gifted mathematician and a trailblazing force whose intelligence and determination fundamentally impacted the U.S. space program and broke down significant racial and gender barriers. Her character was defined by a quiet confidence, an insatiable curiosity, and a deep-seated humility.

atherine Johnson’s story is not just about her mathematical genius but her ability to transcend societal constraints. Her work helped America reach the stars, and her life demonstrated the power of intellect, perseverance, and quiet courage. She once said, “Everything is physics and math,” reflecting her belief in the universal language of numbers—a language she spoke fluently, changing history in the process.

Pingback: The Pioneering Women In Computer Science - Fact Hub

Your article helped me a lot, is there any more related content? Thanks!