The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire-Explained

The Rise and Fall of the Roman Empire spanned centuries of military expansion, political evolution, economic prosperity, and eventual decline, culminating in the collapse of the Western Empire in 476 AD

The rise of Rome (c. 625 BC–27 BC)

Monarchy and Republic: Rome began as a kingdom around 625 BC, advancing militarily and economically before its kings were overthrown in 509 BC. This ushered in the Roman Republic, a system governed by elected officials and the Senate that was meant to prevent any one man from holding too much power.

Expansion through conflict: The Republic grew through a series of conflicts across Italy and the Mediterranean. The Punic Wars (264–146 BC) against Carthage gave Rome control over key territories like Sicily and Spain, establishing it as the dominant maritime power.

From Republic to Empire: As Rome expanded, internal conflicts grew over social inequality and power. Charismatic generals like Julius Caesar gained immense power, eventually leading to civil wars. After defeating his rival Mark Antony, Caesar’s heir, Octavian, became the first emperor, Augustus, in 27 BC, officially ending the Republic and founding the Empire.

The height of the Empire: Pax Romana (27 BC–180 AD)

- A period of peace and prosperity: The first two centuries of the Empire are known as the Pax Romana, or “Roman Peace”.

- This era saw relative peace, political stability, and immense economic growth and prosperity.

- Trade flourished across the vast territory, supported by an extensive network of roads that connected regions from Britain to the Middle East.

- The standardized currency, the silver denarius, also facilitated widespread trade.

- Greatest territorial extent: Under Emperor Trajan (98–117 AD), the Empire reached its maximum size, stretching across three continents and controlling the entire Mediterranean basin.

- Population peak: The population of the Empire is estimated to have peaked at 70 million during the Pax Romana.

The decline and fall of the Western Empire (180 AD–476 AD)

The period following the Pax Romana was marked by a long, gradual decline for the Western Roman Empire, caused by a combination of internal and external factors.

Major factors contributing to the fall

Political instability and corruption

- The vast size of the Empire made effective governance challenging and led to political instability and power struggles.

- From 235 to 284 AD, the “Crisis of the Third Century” saw frequent changes in leadership, civil wars, and a breakdown of centralized power.

- Government corruption and incompetent rulers became common, leading to excessive taxation, inflation, and social unrest.

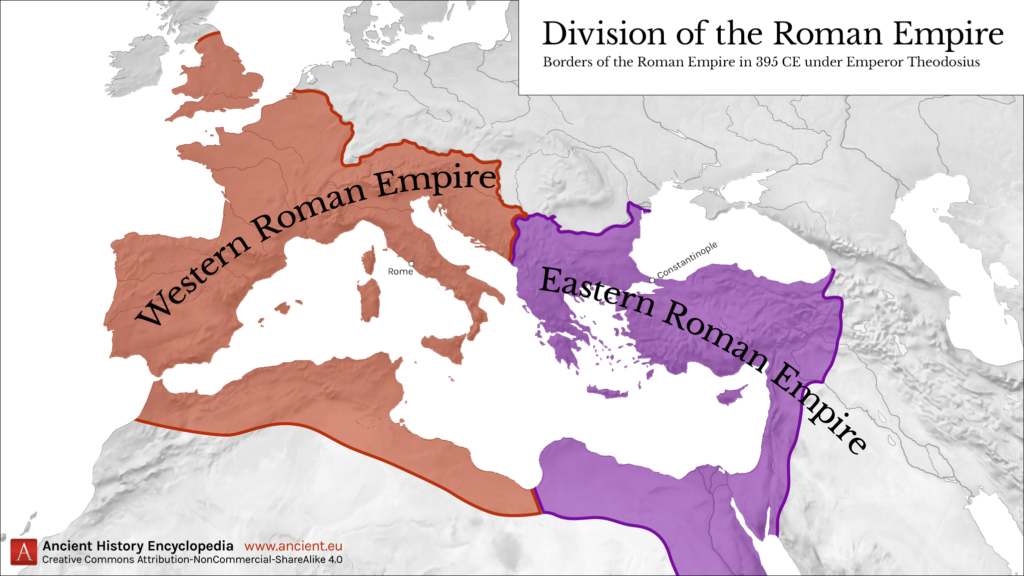

Division of the Empire:

- In 286 AD, Emperor Diocletian divided the Empire into Eastern and Western halves to make it easier to govern.

- This division became permanent in 395 AD, and the wealthier, Greek-speaking East became focused on its capital of Constantinople.

- This shift drained resources and power from the Latin-speaking West, leaving it more vulnerable.

Economic troubles:

-

- The Empire suffered from overspending and an empty treasury due to constant warfare.

- The economic disparity between the wealthy elite and the impoverished population widened, contributing to social unrest.

- Over-reliance on slave labor meant that as the Empire stopped conquering new territories, the supply of free labor dwindled, harming the economy.

Invasions and military issues:

-

- Driven by pressures from groups like the Huns, Germanic tribes began to migrate and raid Roman territories in the 4th and 5th centuries.

- Rome’s inability to repel these attacks strained its resources and led to major sacks of the city in 410 (by the Visigoths) and 455 (by the Vandals).

- The Roman legions themselves weakened. The Empire struggled to recruit enough citizens and increasingly relied on Germanic mercenaries, whose loyalty to Rome was often limited.

Disease and environmental factors:

- Pandemics like the Antonine Plague in the 2nd century caused massive population decline, leading to labor shortages and weakened military strength.

- Some historians also cite climate change and environmental degradation, such as deforestation, as contributing factors to agricultural decline.

The final collapse and Byzantine survival

- In 476 AD, the Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last Western Roman Emperor, Romulus Augustulus, effectively marking the end of the Western Roman Empire.

- While the political structure of the West was gone, the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire, continued to thrive for another millennium.

- The Byzantine Empire, with its capital in Constantinople, preserved many aspects of Roman culture, administration, and law until it fell to the Ottoman Turks in 1453.

The Republic’s transformation into an Empire

The roots of the Empire’s fall can be traced back to the final century of the Roman Republic (c. 133–44 BC).

- Political instability and social conflict: The Republic’s military successes led to immense wealth disparities. Prolonged military service forced small farmers into bankruptcy, increasing the urban and rural poor. Powerful and ambitious generals took advantage of this unrest, using their legions for their own political gain and destabilizing the government.

- Rise of the military dictators: Figures like Julius Caesar gained immense power through military conquest and charisma, subverting traditional republican norms. Following Caesar’s assassination, his heir Octavian defeated his rival Mark Antony in a civil war.

- The birth of the Empire: After his victory, Octavian skillfully consolidated power. In 27 BC, he was granted the title of Augustus, effectively becoming the first emperor and transforming the Republic into an autocratic empire, or “Principate”.

The slow descent: Decline and fall (180 AD–476 AD)

Following the death of Emperor Marcus Aurelius in 180 AD, the Western Roman Empire entered a long period of decline driven by a combination of internal and external factors.

Key internal issues

- Political instability and civil war: The “Crisis of the Third Century” (235–284 AD) saw a rapid turnover of at least 26 emperors, most of whom were generals battling for control. This period of “Military Anarchy” left the frontiers exposed and drained the state of resources.

- Economic deterioration: Chronic warfare led to overspending and a debased currency, causing rampant inflation. High taxes to pay for the bloated military budget stifled trade and commerce, and the gap between the wealthy elite and the impoverished population widened dramatically.

- Division of the Empire: In 286 AD, Emperor Diocletian divided the vast realm into Eastern and Western halves to make it more governable. The more prosperous, Greek-speaking East, with its new capital of Constantinople (founded in 330 AD by Emperor Constantine), was better positioned to withstand the pressures of invasion and internal strife. This division became permanent in 395 AD, leaving the Western Empire weakened and more vulnerable.

- Demographic and social changes: Pandemics like the Antonine Plague in the 2nd century led to severe population decline and labor shortages. As the economy shifted away from major cities toward self-sufficient, fortified estates, the traditional urban lifestyle crumbled. The increasing use of foreign mercenaries also altered the Roman army’s character and loyalty.

External pressures

- The Huns and barbarian migrations: In the late 4th century, pressure from the Huns pushing west caused massive migrations of Germanic tribes, such as the Goths, into Roman territory. The Romans’ inability to effectively manage or repel these large groups escalated tensions.

- Crushing military defeats: A major turning point was the Battle of Adrianople in 378 AD, where the Gothic army inflicted a devastating defeat on the Eastern Roman army, killing Emperor Valens and severely weakening the military’s reputation. This forced Rome to rely even more on barbarian federates.

- The sacks of Rome: The city of Rome itself, once considered invincible, was sacked by the Visigoths under Alaric in 410 AD and again by the Vandals in 455 AD. Although the physical damage was not total, the psychological blow was immense, shattering the myth of Rome’s eternal power.

- The final collapse in the West: By the mid-5th century, the position of Western Roman Emperor was a powerless figurehead. The final blow came in 476 AD when the Germanic chieftain Odoacer deposed the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, and declared himself king of Italy, effectively ending the Western Roman Empire’s political structure.

The Byzantine continuation and Roman legacy

While the Western political structure collapsed, the Eastern Roman Empire, also known as the Byzantine Empire, continued for another thousand years, preserving and evolving Roman laws, culture, and traditions.

- Justinian I’s conquests and legal reforms: In the 6th century, Emperor Justinian I launched campaigns to reclaim former Western territories and codified Roman law in the Codex Justinianus (Code of Justinian). This became the basis for law in many European nations.

- The fall of Constantinople: The Byzantine Empire, based in Constantinople, endured until 1453. The city’s walls were breached by the Ottoman Turks under Sultan Mehmed II. He then adopted the title “Kayser-i Rûm” (Caesar of Rome).

- Enduring influence: The Byzantine Empire’s cultural legacy was significant. It preserved classical knowledge that fueled the Renaissance and acted as a buffer for Western Europe against external threats. The story of Rome’s rise and fall concludes not with a simple collapse, but with a transformation whose enduring influence shaped medieval Europe and continues today.