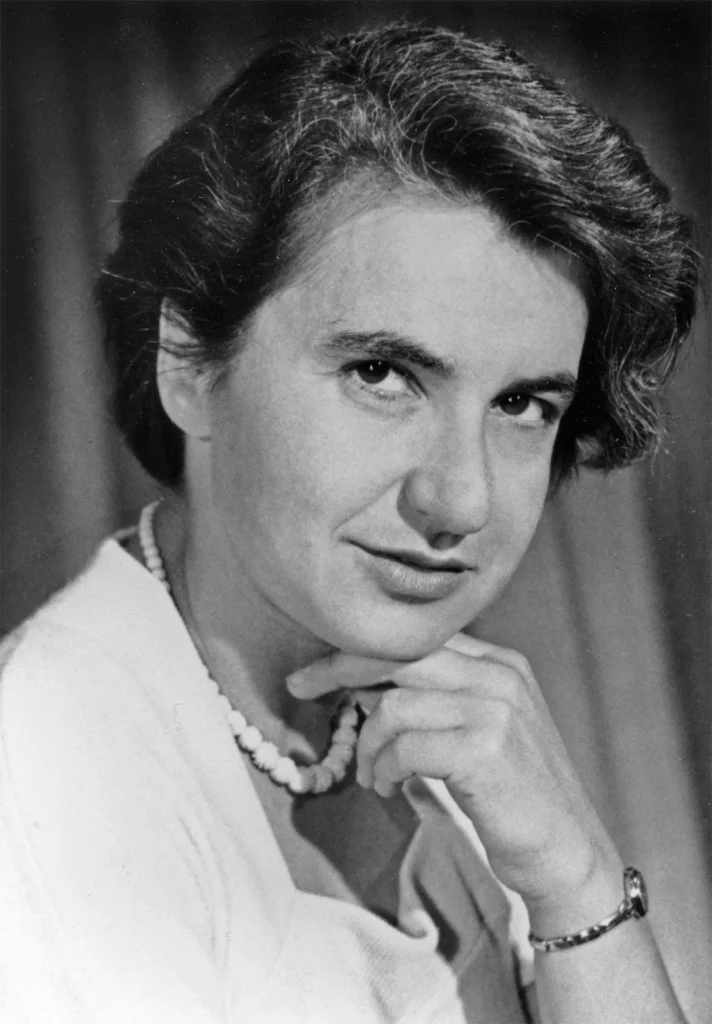

The Life Of Rosalind Franklin and Her Discovery of DNA Structure

Rosalind Elsie Franklin was born on July 25, 1920, in London, England, into a prominent British Jewish family. From an early age, she displayed a keen intellect and a passion for science, excelling in mathematics, physics, and chemistry. At 15, she decided to pursue a scientific career despite societal expectations for women at the time. Franklin attended Newnham College, Cambridge, where she earned a degree in natural sciences in 1941. She went on to pursue a Ph.D. at Cambridge, studying the physical chemistry of carbon and coal, which contributed to wartime efforts through her work on gas masks.

Career and X-Ray

Rosalind Franklin was a highly accomplished chemist and X-ray crystallographer whose research advanced the understanding of the molecular structures of coal, viruses, and DNA. She is best known for her crucial contributions to determining the structure of DNA, which were largely unrecognized during her lifetime.

After graduating from Cambridge, Franklin conducted research at the British Coal Utilisation Research Association (BCURA) during World War II.

She studied the molecular structure and porosity of coal, work that proved valuable for classifying coals and developing gas masks for the war effort.

This research earned her a Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Cambridge University in 1945.

From 1947 to 1950, she worked in Paris under Jacques Mering, who taught her advanced X-ray crystallography techniques. She applied these methods to study the properties of carbon and its conversion to graphite, becoming an international authority on the subject.

- In 1951, Franklin accepted a research fellowship at King’s College London to study proteins and lipids.

- Upon her arrival, she was unexpectedly reassigned to work on DNA fibers using X-ray diffraction, a role she would share uneasily with colleague Maurice Wilkins.

- At King’s, Franklin’s rigorous experimental approach led her to discover that DNA existed in two forms, “A” and “B,” depending on humidity.

- Her careful technique produced significantly clearer X-ray images than her colleagues had previously obtained.

Work on viruses at Birkbeck College

- Following a tense working environment at King’s, Franklin moved to Birkbeck College in 1953 to lead her own research group.

- Her focus shifted to the molecular structures of viruses, including the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV).

- She and her team published several seminal papers on the subject, establishing the foundations of structural virology.

- She died tragically of ovarian cancer in 1958 at the age of 37.

Franklin’s X-ray crystallography and the DNA discovery

Photo 51

- In May 1952, Franklin and her graduate student, Raymond Gosling, used X-ray crystallography to capture an image of the “B” form of DNA. This image, known as “Photo 51,” was a groundbreaking diffraction pattern that revealed the helical structure of the molecule.

Unshared data

- Unbeknownst to Franklin, Maurice Wilkins showed Photo 51 to James Watson, who was also researching the structure of DNA with Francis Crick at Cambridge.

- Watson and Crick also had access to a research report from a Medical Research Council visit to King’s that contained some of Franklin’s crucial crystallographic calculations.

The double helix

- Using Franklin’s unpublished data from Photo 51 and her calculations, Watson and Crick were able to construct their model of the DNA double helix.

- Their paper detailing the structure was published in Nature in April 1953, alongside papers from Wilkins and Franklin.

- Though her work corroborated their model, the footnotes in the Watson and Crick paper only offered a minimal acknowledgment of her contribution, based on a deal between the laboratory directors.

The Discovery of DNA’s Structure

The discovery of the structure of DNA was a monumental scientific achievement that involved multiple researchers, most famously James Watson, Francis Crick, and Rosalind Franklin. Their work revealed the double-helical shape of the DNA molecule, which explained how genetic information is stored, replicated, and passed down through generations.

Rosalind Franklin (1920–1958): The X-ray crystallographer

- Experimental evidence: A physical chemist, Franklin was an expert in X-ray crystallography. At King’s College London, she conducted rigorous and methodical research that produced the clearest X-ray diffraction images of DNA ever seen.

- Photo 51: Her graduate student Raymond Gosling captured the famous “Photo 51” in May 1952, which provided undeniable evidence of a helical structure. The distinctive “X” shape in the image was a key clue.

- Overlooked contribution: Without Franklin’s knowledge, her colleague Maurice Wilkins showed Photo 51 to James Watson. The image, along with Franklin’s detailed unpublished reports, was critical for Watson and Crick’s model-building.

- Posthumous recognition: Franklin died of ovarian cancer in 1958, four years before Watson, Crick, and Wilkins received the Nobel Prize. Her critical contributions were largely unrecognized during her lifetime, leading to significant controversy.

James Watson (b. 1928) and Francis Crick (1916–2004): The model builders

- Cavendish Laboratory: The two worked together at the Cavendish Laboratory in Cambridge, combining data from various researchers to deduce the final structure.

- The double helix model: Using Franklin’s X-ray data and Erwin Chargaff’s rules on base pairing (A pairs with T, and C with G), they constructed a physical model of the DNA double helix.

- Publication: They published their findings in a one-page paper in the journal Nature on April 25, 1953, with a drawing of the proposed double helix. In it, they famously noted that the base pairing “immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material”.

Maurice Wilkins (1916–2004): The biophysicist

- Early X-ray work: Wilkins was one of the first to apply X-ray diffraction techniques to DNA and was in charge of the DNA project at King’s College London when Franklin joined.

- Role in communication: His strained relationship with Franklin led him to share her unpublished data, including Photo 51, with Watson and Crick.

- Verification: Following the publication of the Watson and Crick model, Wilkins and his team continued to produce X-ray data that confirmed the double-helix structure.

- Nobel Prize: He shared the 1962 Nobel Prize with Watson and Crick.

Erwin Chargaff (1905–2002): The biochemist

- Chargaff’s rules: In 1949, Chargaff discovered that in DNA, the amount of adenine (A) always equals the amount of thymine (T), and the amount of cytosine (C) always equals the amount of guanine (G).

- Crucial data: This discovery was a vital piece of the puzzle that Watson and Crick used to deduce the base-pairing mechanism that holds the two strands of the double helix together.

- 1949: Biochemist Erwin Chargaff publishes his findings, later known as Chargaff’s rules, showing that A=T and C=G in DNA.

- 1951: Rosalind Franklin joins King’s College London and begins using X-ray crystallography on DNA.

- May 1952: Franklin’s student Raymond Gosling takes “Photo 51,” the clearest image of B-form DNA, at King’s College.

- January 1953: Maurice Wilkins shows Photo 51 to James Watson without Franklin’s knowledge or consent.

- March 1953: Watson and Crick complete their double-helix model of DNA at Cambridge’s Cavendish Laboratory.

- April 25, 1953: Watson and Crick publish their findings in Nature. Two accompanying papers from King’s, one by Wilkins and a separate one by Franklin and Gosling, provide supporting evidence.

- 1958: Rosalind Franklin dies of ovarian cancer.

- 1962: James Watson, Francis Crick, and Maurice Wilkins are awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine.

Legacy Of Rosalind Franklin

Rosalind Franklin’s legacy extends far beyond her critical contribution to discovering the structure of DNA. While the story of her crucial “Photo 51” being used without her consent casts a shadow over the history of science, her legacy is a testament to her technical brilliance, meticulous work ethic, and groundbreaking research in multiple fields.

Pioneering structural biology: Franklin’s mastery of X-ray crystallography laid the groundwork for structural biology. She refined the technology to achieve unprecedented clarity in her images, a technique still foundational to understanding complex biological molecules. This approach has influenced fields from genetics to virology.

- Viral genetics and structure: After leaving her DNA work, Franklin became a leader in the field of structural virology. Her research on the tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) and the polio virus proved that the RNA in TMV was a single-strand helix and established the foundational knowledge for how viral particles are structured. Her work in this area continued after her death, with her colleague Aaron Klug winning a Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1982 for research they began together.

- Foundational work on carbon: Long before her DNA research, Franklin’s work on the physical chemistry of coal and graphite was crucial for the war effort and valuable to the coking industry. Her discoveries concerning the porosity and structure of carbon-based materials are still relevant in materials science today.

- Fueling advancements in genomics: The understanding of DNA’s double helix structure, to which Franklin so critically contributed, paved the way for modern genomics and personalized medicine. Tools like CRISPR and gene sequencing all build on the foundational knowledge of how genetic information is stored and transmitted.

A symbol for women in STEM

- Breaking barriers: Franklin faced significant hurdles as a woman in the male-dominated scientific world of the 1940s and 50s. Despite these obstacles and the historical dismissal of her contributions, she remained fiercely dedicated to her work and maintained her identity as a scientist.

- Inspiring future generations: Her story has become a touchstone for discussions about gender bias in science and the importance of crediting the contributions of all researchers. Her example has encouraged countless girls and young women to pursue careers in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM).

- The “wronged heroine”: The posthumous recognition of Franklin’s role in the DNA discovery has led to her being dubbed the “forgotten heroine” and a “feminist icon”. Her story reminds the scientific community and the public to be more vigilant about inclusion and acknowledging diverse voices in research.

Lasting tributes and honors

- Institutional recognition: Franklin’s contributions are now widely celebrated by the scientific community. Numerous awards, institutes, and scholarships are named in her honor, including the Rosalind Franklin University of Medicine and Science in Chicago and the Rosalind Franklin Institute in the UK.

- Cultural legacy: Her life and work are the subjects of documentaries, books, and plays, which have brought her story to a wider audience. In 2019, the European Space Agency named its ExoMars rover “Rosalind Franklin”. These tributes help cement her place in history as a brilliant and determined scientist.

Franklin’s X-ray diffraction images and precise measurements provided critical data that shaped our understanding of DNA, enabling advancements in genetics, biotechnology, and medicine. Her story highlights the challenges faced by women in science during the mid-20th century and underscores the importance of equitable recognition in scientific discovery. Institutions, awards, and buildings now bear her name, and her legacy continues to inspire scientists worldwide.