The Brilliance of Marie Curie

Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867–1934) stands as one of the most iconic figures in the history of science, a trailblazing physicist and chemist whose groundbreaking work on radioactivity not only reshaped our understanding of the atomic world but also paved the way for transformative advancements in medicine, energy, and beyond. Born in Warsaw under Russian occupation, her journey from a clandestine education in occupied Poland to becoming the first woman to win a Nobel Prize—and the only person to win in two different scientific fields—exemplifies resilience, intellectual brilliance, and an unyielding commitment to discovery. This essay, spanning approximately 1,800 words, weaves a comprehensive biography of Marie Curie with an exploration of her enduring brilliance, drawing on her personal struggles, scientific achievements, and lasting legacy. By examining her life through the lens of perseverance and innovation, we uncover how Curie’s brilliance lay not just in her discoveries but in her ability to illuminate paths for future generations, particularly women in science.

Seeds of Brilliance in Adversity

Maria Salomea Skłodowska—later known as Marie Curie—was born on November 7, 1867, in Warsaw, in what was then the Kingdom of Poland under Russian imperial rule. The youngest of five children in a family of educators, Marie grew up in an intellectually stimulating yet financially strained household. Her father, Władysław Skłodowski, was a respected mathematics and physics teacher, while her mother, Bronisława, managed a prestigious girls’ boarding school before succumbing to tuberculosis when Marie was just ten years old. This early loss profoundly shaped her, instilling a stoic determination that would define her career. The Russian suppression of Polish culture, including bans on higher education for women, forced Marie and her sister Bronisława to seek clandestine learning at the “Flying University,” a secret institution that operated in rotating locations to evade authorities. Here, Marie excelled in physics and chemistry, honing the analytical mind that would later unlock the secrets of the atom.

she even conducted informal experiments with her students. In 1891, at age 24, she joined Bronisława in Paris, enrolling at the Sorbonne University. Living in abject poverty—often surviving on buttered bread and tea—Marie graduated first in her physics class in 1893 and followed with a master’s in mathematics the next year. This period revealed her innate brilliance: not merely rote intelligence, but a profound curiosity that transformed obstacles into opportunities. As she later reflected, “Nothing in life is to be feared, it is only to be understood.” Her early life in occupied Poland forged a resilience that would prove essential in the male-dominated world.

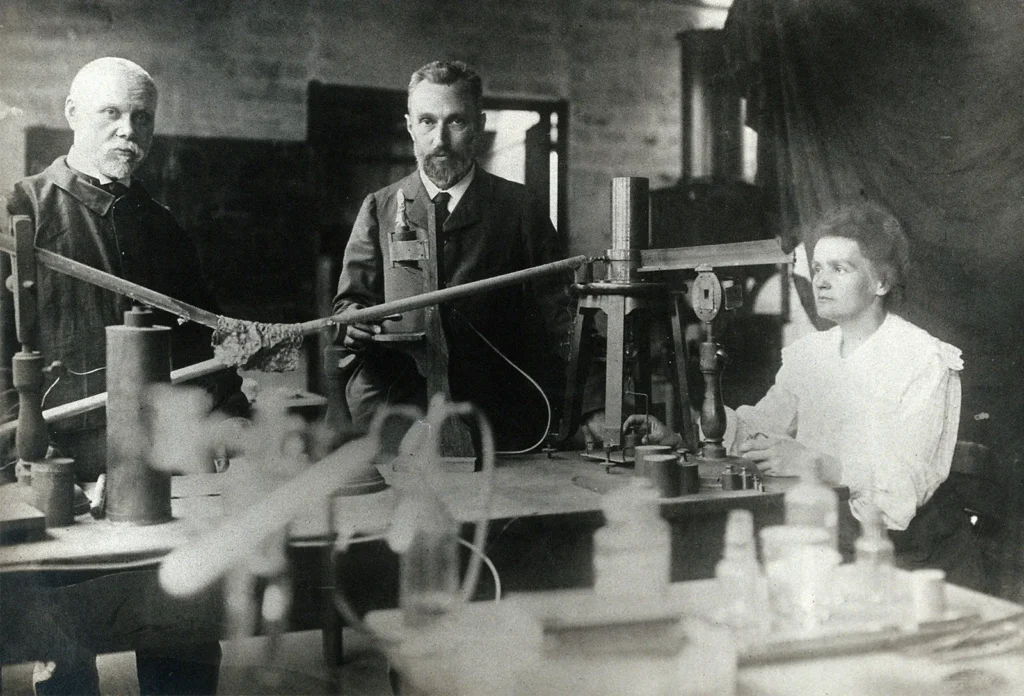

Meeting Pierre Curie

In 1894, while researching the magnetic properties of steels for her doctoral thesis, Marie was introduced to Pierre Curie, a 35-year-old physicist renowned for his work on piezoelectricity and magnetism. Their collaboration began professionally but swiftly evolved into a profound intellectual and romantic partnership. Pierre, struck by Marie’s rigor and passion, abandoned his own research to join hers. They married in 1895 in a simple civil ceremony—eschewing the Catholic rites of Marie’s upbringing—symbolizing their shared commitment to science over tradition.

The Dawn of Radioactivity

The late 1890s marked the pinnacle of the Curies’ collaborative brilliance. Inspired by Henri Becquerel’s accidental discovery of uranium’s spontaneous radiation in 1896, Marie embarked on a systematic study of radioactive minerals. Her thesis, “Radioactive Substances,” introduced the term “radioactivity”—a coinage that encapsulated her conceptual leap: that atoms themselves could decay and emit energy. Processing tons of pitchblende ore in their rudimentary shed, the Curies isolated two new elements in 1898: polonium (named for Marie’s homeland, a subtle act of patriotic defiance) and radium, which glowed with an otherworldly intensity 400 times greater than uranium.

Curie’s discoveries were not abstract; they were luminous acts of illumination. Radium’s eerie glow symbolized her ability to pierce the veil of the unknown, transforming invisible forces into tangible wonders. Her brilliance lay in bridging theory and practice, coining concepts that propelled nuclear physics forward.

Trials and Triumphs: Scandal, War, and Legacy

Curie’s brilliance was tested by personal and societal tempests. In 1911, a public scandal erupted over her affair with physicist Paul Langevin, Pierre’s former student, tarnishing her reputation amid France’s sexist undercurrents. Yet, she pressed on, defending her Paris laboratory from mobs and securing her Nobel amid controversy. During World War I, her ingenuity birthed the “Little Curies”—portable X-ray machines mounted on vans, which she personally drove to battlefields, training women as radiological technicians to save countless lives by locating shrapnel and fractures. Over 1 million soldiers benefited from these units, a humanitarian application of her science that underscored her practical genius.This mother-daughter legacy highlights Curie’s brilliance as a mentor; she empowered women like Marguerite Perey (discoverer of francium) and Ellen Gleditsch, creating a network of female trailblazers in a field dominated by men. Her international advocacy, including membership in the League of Nations’ Intellectual Cooperation Committee, amplified her influence, as did her 1923 biography of Pierre, which humanized their shared triumphs.

Marie Curie’s Contributions to Radioactivity and Science

Marie Skłodowska Curie (1867–1934) is a towering figure in the history of science, whose pioneering work on radioactivity fundamentally transformed our understanding of the atomic world and revolutionized multiple scientific fields. As the first woman to win a Nobel Prize and the only person to win Nobel Prizes in two different sciences—Physics (1903) and Chemistry (1911)—Curie’s contributions extended beyond theoretical breakthroughs to practical applications that reshaped medicine, physics, and chemistry. This essay, spanning approximately 1,500 words, explores Curie’s groundbreaking contributions to radioactivity, her methodological innovations, her impact on medical science, and her enduring legacy in fostering scientific inquiry, particularly for women in STEM.

Marie Curie’s most profound contribution to science was her pioneering research on radioactivity, a term she coined to describe the spontaneous emission of energy from certain elements. Her work built on Henri Becquerel’s 1896 discovery that uranium emitted rays capable of penetrating solid matter and fogging photographic plates. While Becquerel’s finding was accidental, Curie transformed it into a systematic scientific inquiry, hypothesizing that radioactivity was an atomic property rather than a molecular one—a revolutionary idea that challenged the prevailing view of the atom as indivisible.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 10</grok:render>

In her 1903 doctoral thesis, Recherches sur les substances radioactives (Radioactive Substances), Curie meticulously measured the radiation emitted by various minerals using an electrometer designed by her husband, Pierre Curie. Her methodical approach revealed that radioactivity was not limited to uranium but was present in other substances, such as thorium. This insight led to her most celebrated achievement: the discovery of two new elements—polonium and radium—in 1898.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 3</grok:render>

Working in a rudimentary shed at the École Municipale de Physique et Chimie Industrielles in Paris, the Curies processed tons of pitchblende ore, a uranium-rich mineral, to isolate minute quantities of these elements. Polonium, named in honor of Marie’s native Poland, was 400 times more radioactive than uranium, while radium was over a million times more potent, glowing with an eerie luminescence that captivated the public and scientific community alike.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 1</grok:render> The isolation of radium in its pure metallic form by 1910, a feat accomplished solely by Marie after Pierre’s death in 1906, cemented her reputation as a master chemist and earned her the 1911 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 11</grok:render>

Curie’s discovery of radioactivity redefined atomic physics by demonstrating that atoms could disintegrate, emitting alpha, beta, and gamma rays. This challenged the classical model of the atom and laid the groundwork for nuclear physics, influencing later discoveries like nuclear fission and the development of quantum mechanics.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 14</grok:render> Her work provided the first evidence that matter was not static but dynamic, opening new avenues for understanding energy at the subatomic level.

Her use of the electrometer to quantify radiation was a technological leap. By measuring the ionization caused by radioactive emissions, Curie provided a standardized method to compare the intensity of different substances, establishing a quantitative foundation for radioactivity research.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 10</grok:render> This precision enabled her to identify polonium and radium and laid the groundwork for subsequent studies of radioactive decay chains.

Curie’s approach was interdisciplinary, blending physics and chemistry in a way that was novel for her time. Her collaboration with Pierre, whose expertise in crystallography complemented her chemical acumen, exemplified this synergy. Together, they developed instruments and techniques that became standard in laboratories worldwide, such as the piezoelectrically driven electrometer for detecting radiation.<grok:render type=”render_inline_citation”> 1</grok:render> Marie’s insistence on empirical rigor and her ability to translate abstract phenomena into measurable outcomes set a benchmark for experimental science.